It has always been the most inconvenient and disturbing truth about a Dodgers franchise that decamped from Brooklyn and bloomed anew in this gorgeous nook of Los Angeles called Chavez Ravine: That to build what became Dodger Stadium, arguably the greatest diamond of them all, nearly 2,000 families, most of them of Mexican-American descent, were strong-armed and coerced and eminent-domained out of their homes.

It was the ugliest bait-and-switch: Public housing, ostensibly hosting even more families, was set to emerge from the Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop communities, but instead, it was set aside for a sports team, turbocharging an era when public subsidies and land grabs would enrich owners and boost their franchise values.

Less tangible: The mountains of generational wealth wiped away with those homes, and this year, California legislators aimed to pass the Chavez Ravine Accountability Act, a bill that would seek to provide reparations to displaced families. It was vetoed by Gov. Gavin Newsom earlier this month.

Yet the baseball gods, such as they are, work in the strangest ways, equally cool and cruel.

Follow every MLB game: Latest MLB scores, stats, schedules and standings.

Less than two decades after Dodger Stadium opened in 1962, 22 years after the club landed from Brooklyn, Fernando Valenzuela blessed the land with his arrival from Mexico. Just 20 years old, born in that between time of 1960 when the Dodgers played their games at the Coliseum, he was a baseball comet, landing at the tail end of 1980 and producing the greatest, or at least most notorious, rookie season for a pitcher in baseball history.

Fernandomania cannot be replicated, neither in the stunning first five weeks of the 1981 season when he started eight games, completed seven of them, posted a 0.50 ERA, tossed five shutouts and ignited a new era of runaway prosperity for the Dodgers.

Nor will we likely see a rookie season finished in the manner Fernando did it: A 147-pitch complete game to stifle the New York Yankees in Game 4 of the World Series to take a commanding 3-1 lead – just a week before his 21st birthday.

The Dodgers would close out those Yankees in six games, sweetening part of the bad taste from losing consecutive Series to them in 1977-78.

And with Fernando on the mound and an increasingly diverse audience watching from the Dodger Stadium seats, or listening to the sweet tones of Vin Scully or Jaime Jarrin on a transistor radio, the Dodgers became the behemoth franchise they are today.

Funny thing about displacement, borders, and odious xenophobia: They can’t stop progress, nor prosperity.

And goodness, did the post-Fernando Dodgers prosper.

Their 1978 run to the NL pennant drew a franchise-record 3.3 million fans to Dodger Stadium, but attendance dropped below 3 million two years later. The year of Fernandomania was sullied by a work stoppage, limiting the season to 110 games.

Strike years tend to have a dampening effect, sometimes lasting decades, on disgruntled fans. But the year-after bump from a World Series title and a young lefty looking toward the heavens lured a record 3.6 million fans through the Dodger Stadium gates in 1982.

L.A. was changing and so, too, was the Dodger fan base: If the smiling visage of ostensibly All-American first baseman Steve Garvey was the face of the 1970s Dodgers, it was eventually complemented by Latino stars such as Valenzuela, Pedro Guerrero, and eventually Ramon and Pedro Martinez.

And in Fernando, a Mexican-American community often confined to L.A.’s shadows had a hero to celebrate. Los Angeles, a company town whose machinations would not be possible without the contributions of immigrants coming from Mexico for a better life or fleeing the strife of Central America, was suddenly, truly reflected among its fan base.

That growth at the turnstiles? It hasn’t stopped. Certainly, it was slowed by the incompetent ownership stint of News Corp. and the utter pillaging of the franchise by Bostonian Frank McCourt, but the Dodgers have not drawn less than 3.7 million fans since 2013.

The Dodgers’ new ownership group certainly understands investment and growth, and the $700 million investment in Shohei Ohtani maxed out the ancient ballyard’s capacity: Nearly 4 million fans, tops in the majors, and rolling some 50,000 deep even for the proverbial midweek night in April against the Diamondbacks.

And oh, what a team: Shohei and Yoshi and Teo and Mookie and Kiké and Freddie, 98-game winners, NL champions, playing to packed houses every night.

It might be too loud for some, but it’s undoubtedly a damn party for a fan base that could not celebrate a championship during the pandemic year of 2020. They roar to the cues of organist Dieter Ruehle and groove to the unsparing tones of favorite son Kendrick Lamar, just like their melting pot of a clubhouse.

Friday night, it will all coalesce with baseball’s ultimate matchup: Yankees-Dodgers, Game 1 of the World Series, an undeniable SoCal tint to it all. Jack Flaherty will face off against Gerrit Cole, a biracial kid from the Valley vs. a white dude from Orange County, 818 vs. 714 in the 323, a composition not unlike the 50,000-plus paying a lot of money to witness it.

And this is where the baseball gods, such as they are, flex their occasional abject cruelty.

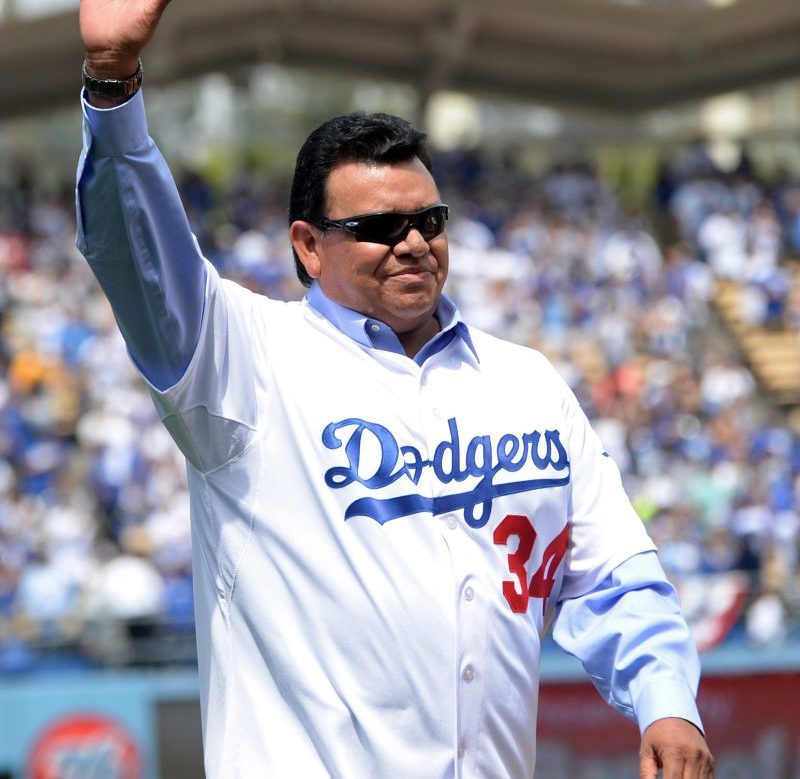

Valenzuela, whose number was finally retired two seasons ago, whose voice and image lent regality to the Dodgers’ Spanish-language TV and radio broadcasts, will not be there. His death at 63 Tuesday night comes at the cruelest moment, the West Coast’s solemn version of Willie Mays’ tragic passing just days before Major League Baseball honored him at Birmingham’s historic Rickwood Field.

Now, Game 1 will be a makeshift memorial, not unlike Rickwood, a time to mourn a loss but also appreciate that an extended family will be together to do so.

There likely won’t be any odes to the families that once occupied that land, and those seeking to make them whole are now back to the drawing board. The Dodgers have won five World Series titles there, but they’re simply ballplayers, unable to correct such heavy injustices.

And Fernando was just a pitcher. But what he built in Chavez Ravine will last forever.

The USA TODAY app gets you to the heart of the news — fast. Download for award-winning coverage, crosswords, audio storytelling, the eNewspaper and more.